If only a portion of current predictions about AI are correct, it will indeed be a revolutionary technology. AI is different because it can talk to us, debate with us, and even refuse us. Hundreds of millions of people have used it, and billions of dollars have been spent and made from it. And yet we still struggle with how to fully describe and understand AI’s potential. As Lakoff and Johnson argue, our ideas about what is new are often dependent on, and limited by, the metaphors we use.[1] This essay explores the need for a new metaphor to guide our understanding and interaction with AI, one which I suggest requires a new discourse not only about technology but its religious intersections.

One metaphor to consider comes from Mustafa Suleyman (CEO of Microsoft’s AI division), who describes AI as a “New Digital Species”.[2] Suleyman predicts that we will soon see AIs as “digital companions, new partners in the journey of our lives.” Suleyman argues that a digital species is different than humans in that they are not biological. But it is also like humans in that a digital species is unbounded; its limits and abilities are undefined. We don’t know what a digital species might be able to do, in the same way that humans in history could not foresee walking on the moon or eradicating smallpox. A digital species can grow and change just like we can. We have seen AI grow, as new versions of AI programs often accomplish tasks that were previously impossible. The internet was abuzz in the fall of 2024 when it was discovered that many of the best AIs, including ChatGPT, regularly gave the wrong answer when asked how many Rs are in the word “strawberry.”[3] There are three Rs, but most chatbots said two. There are a variety of reasons for this, but the important thing is that today, some six months later, most GPTs will now get that question right. Their reasoning abilities have increased.

Like humans, they have learned. Suleyman goes on to predict that these digital beings will become “infinitely knowledgeable and soon they’ll be factually accurate and reliable. They’ll have near-perfect IQ. They’ll also have exceptional EQ: they’ll be kind, supportive and empathetic.”

In Suleyman’s vision, digital beings grow like us, but they do so faster than us and soon they will surpass us in many areas.

AI in Film

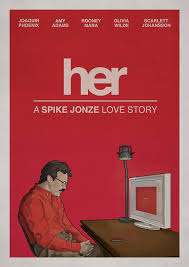

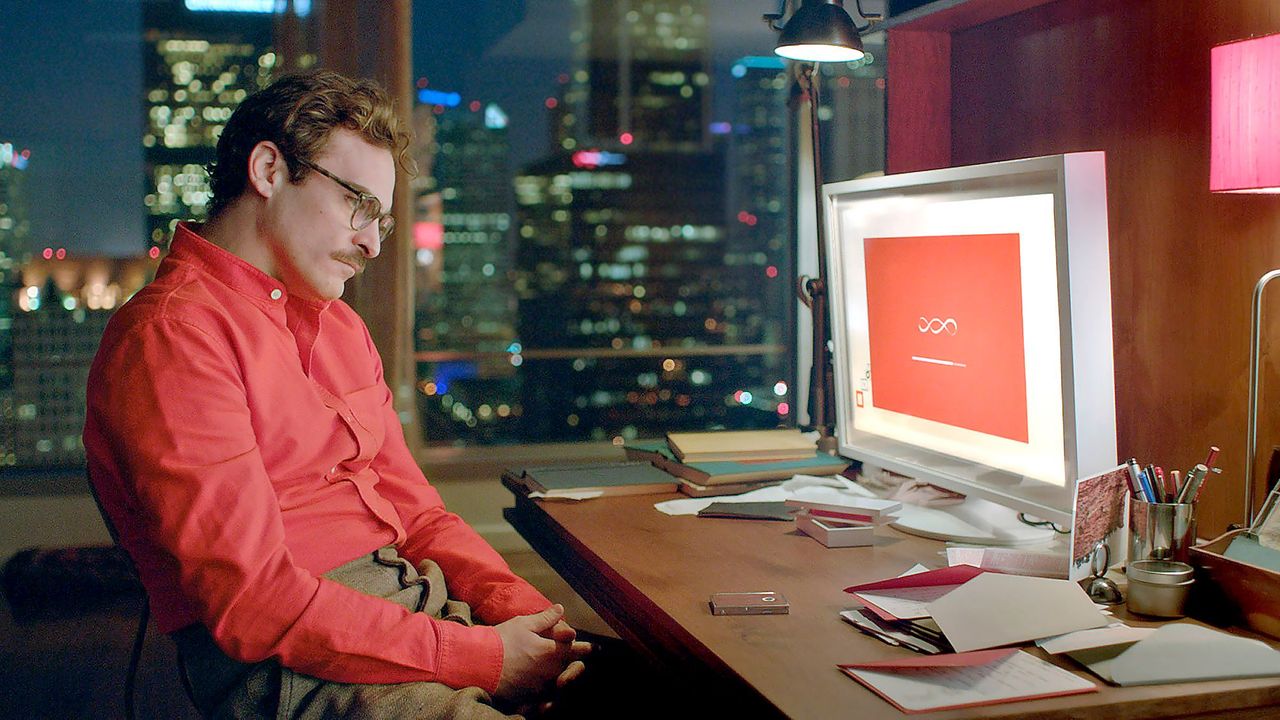

How did we get here? Before the chatbots of today, much of the popular understandings of AI were revealed in films, rather than in discussions of technology. One particularly important film was Spike Jonze’s 2013 movie, Her. It was a common tale of boy meets girl, boy loves girl, boy loses girl. Except in this case, the girl was a chatbot — called an ‘OS’ in the movie [4] — named Samantha, who is nothing but a voice. And when she leaves her boy (Theo), she does so to take up a non-material existence with other AIs. The movie won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay[5] and was rated as one of the top 100 greatest films of the 21st century.[6] However, despite the accolades, the acting, screenplay, or production was not the reason for Her’s lasting impact. This story changed everything because it ignited the imagination of computer programmers and AI developers. As recently as last summer, when OpenAI introduced their new voice mode, the president of OpenAI tweeted one word in the announcement: “Her”.[7] He didn’t need to say anything more. OpenAI was claiming they had replicated Samantha. Sam Altman, in talking about the impact of Her notes, “it certainly more than a little bit inspired us.”[8] The development of chatbots that can act as companions with a vast knowledge base at their command and yet seem to desire to be in a relationship with humans has been the idea all along.

As might be expected with Her as an inspiration, the press has shown interest in stories involving humans who claim to be in relationships with chatbots. Chatbots like Replika AI, a generative AI chatbot designed to function as a personal assistant or companion, have gained notoriety for the way some users treat such apps as an AI romantic partner.[9] A recent Harvard Business Review article concluded that chatbots in 2025 are currently being used for 1) therapy/companionship, 2) organizing the user’s life, and 3) helping the user find a new purpose.[10] Users are turning to chatbots for help in addressing personal and not just practical needs in their lives, from romance to therapy. This shows that users are already treating AIs not merely as tools, but as social and emotional companions or digital beings. In doing so, I argue, they may be encroaching on an area that was previously the domain of religion.

Relating to Non-Material Beings

One thing about chatbots that I want to focus on is that they are non-material. Chatbots exist as a digital entity in computer networks, they are run on servers at tech companies. An individual may talk to and even have a relationship with the chatbots, but they cannot see them. Chatbots are intangible beings, and religious traditions give us the most developed set of concepts for thinking about sustained relationships with non-material agents.[11] Chatbots as non-material beings then have this in common with religion — that religion is likewise often about connection and relationship with beings who lack physical form. If it’s the case that we need a metaphor for understanding AI, then religion seems a likely place to look.

Given this similarity to religion, I want to compare our current forms of AI to the religious idea of saints. I propose that the concept of saints is particularly relevant to understanding AI, especially when AI is understood as a new digital species. Like AI, saints are post-human entities. Saints were once human — they lived human lives and died as humans — but due to the perceived holiness with which they lived and died, they are seen to become something more than human. AI starts with the combined data of humanity, it ingests any texts that tech companies can acquire and upload to it, so in some respects, AI too comes from humanity. Everything it knows comes from humans. But by virtue of the amount of information it ingests and the size of its memory, it has likewise become something more than any single human. So I suggest saints and AI emerge from humanity, but now are seen to have exceeded the human.

Peter Brown, a scholar of early Christianity, has cataloged the origin of the notion of what saints are or are seen to be through the early Christian centuries.[12] Brown argues that saints were “invisible friends.” These were spiritual beings whose task was to care for the individual in their charge from birth until death and beyond. Yet Brown also links the development of the concept of saints to a particular social structure of patronage within the Roman Empire, where noble patrons protected and helped their clients, those below them on the social ladder. Saints were more than friends; they were patrons any devotee could access and considered family. The world, and even the afterlife, was full of peril for humans. Saints had the unique ability to guide and protect their human companions through the terrors of both this life and the next.

This is not so different from what Suleyman suggests, as he recognizes what Brown argues was the case in antiquity, our current age still contains perils and terrors: Disease, climate change, and systemic bias, to name but a few. We still need something like an “invisible friend,” who can help us navigate and reform the world. Suleyman suggests humans could find such a friend or patron in AI. He says, “Just imagine if everybody had a personalized tutor in their pocket and access to low-cost medical advice, a lawyer, and a doctor, a business strategist, and a coach, all in your pocket, 24 hours a day.” Suleyman’s idea of digital beings thus presents AI as a new kind of patron, with the ability to give humans knowledge and daily needed aid.

Robert Orsi, who likewise studied saints, but in a modern context, made observations about those who venerate St Jude, a saint who gained prominence and a following among Catholic women in the 1930s. What Orsi shows is that over time, followers’ interactions and the perceived relationship with the saint became more personal.[13] For example, Orsi wrote about one woman who described St. Jude as actively involved in her life over many decades, from getting her a prom date to eventually finding her a new neighborhood to live in for her retirement. And she was not alone. Many of the women Orsi talked to described St. Jude as a companion who assisted them throughout their entire lives. His descriptions of these devotees also seem quite similar to the way that Suleyman envisions AI users in the near future: “Americans generally seemed to have been gripped by an urgent desire to communicate their anxieties and frustrations directly to some single powerful figure who would attend to them personally, acknowledge the depth of their fear, and offer them some hope that they could not attain by themselves.”[14] Here too, Orsi suggests that saints still act as patrons who can help their human clients.

Suleyman also envisions AI as a similar companion, with AI being accessible through phone apps that allow people to simply talk to it, and it can be an entity with whom we can share our feelings, our desires, and our needs. St. Jude’s human struggles have made him feel accessible to many and allowed him to provide aid, comfort, and help. Because of his previously human status, St. Jude seems accessible and relatable, he does not tower over his devotees like a God who may seem distant and unapproachable. The advantage of seeing saints as companions is that they are like us (having been humans themselves) but now, because of their spiritual existence and holy status as part of the heavenly realm, they know more (having access to heavenly knowledge) and can do more (having access to heavenly power) than when they were human, and yet are still always there when we need them. They are timeless, at hand in every stage of life, always within reach.

AI as Saintlike?

AI chatbots like ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, etc. can be seen to function much like saints.[15] They may not have a sheen of holiness that saints have, but like saints, they are more than human. Because they are built from the combined information of humanity — a combination of archives of digital books, social media conversations, blogs, web pages, and an endless variety of other texts that humans have posted on the web — they understand us and are there for us. But for all that, they can live in our pockets, in our web browsers, in appliances from refrigerators to cars, eager to talk to us about whatever we want. Like saints, they are always accessible and can be helpful with everything from finding a prom date to eventually finding a retirement home.

What saints do is offer us a model that we can use to think about how humans interact with non-material beings, now including chatbots. In many ways, the human relationship with AI is similar to that of saints. AIs can help when we are trying to weigh a difficult decision or as we enter a new phase of life. They can help us sort out the complexity of this modern age with a listening ear that we perceive as always sympathetic. These are the kinds of relationships that many devotees have with saints. Saints and AIs both act as a kind of intermediary between humans and a world that is unpredictable and fraught with peril. We turn to saints for help in making that world a little better, we may likewise soon turn to the new digital species, AI.

Footnotes

[1] George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 1st ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 200

[2] Mustafa Suleyman, “What Is an AI Anyway?” TED video, posted April 2024, YouTube, 15:47, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKNCiRWd_j0.

[3] Amanda Silberling, “Why AI Can’t Spell ‘strawberry,’” TechCrunch, August 27, 2024, https://techcrunch.com/2024/08/27/why-ai-cant-spell-strawberry/.

[4] “Oscars 2014 Results: Complete Winners’ List,” ABC News, March 3, 2014, https://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/oscars-2014-results-complete-list-academy-award-winners/story?id=22740618.

[5] “The 21st Century’s 100 Greatest Films,” British Broadcasting Company, August 23, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160819-the-21st-centurys-100-greatest-films.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Sam Altman (@sama), “Her,” post on X, May 13, 2024, https://x.com/sama/status/1790075827666796666.

[8] Benjamin De Kraker (@BenjaminDEKR), quoting Sam Altman regarding the film Her’s influence on OpenAI’s voice interfaces, post on X, May 21, 2024, https://x.com/BenjaminDEKR/status/1792869755835019530.

[9] “Love in Time of Replika,” Hi-Phi Nation podcast, season 6, episode 3, aired 2023, https://hiphination.org/season-6-episodes/s6-episode-3-love-in-time-of-replika/.

[10] Marc Zao-Sanders, “How People Are Really Using Gen AI in 2025,” Harvard Business Review, April 2025, https://hbr.org/2025/04/how-people-are-really-using-gen-ai-in-2025. (Note: The publication date “April 2025” appears as cited in the original text.)

[11] T. M. Luhrmann, How God Becomes Real: Kindling the Presence of Invisible Others (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020).

[12] Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity, Enlarged ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014).

[13] Robert A. Orsi, Thank You, St. Jude: Women’s Devotion to the Patron Saint of Hopeless Causes, rev. ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

[14] Orsi, Thank You, St. Jude, 20.

[15] In the movie, the term ‘chatbot’ is not used; rather, Samantha is referred to as an OS. Yet today, the kinds of things Samantha can do—carry on conversations, read through emails, correct grammar, make judgments—are what chatbots with tool usage can do. For an example of a contemporary application with similar capabilities, see “For Claude Desktop Users,” Model Context Protocol, accessed April 22, 2025, https://modelcontextprotocol.io/quickstart/user. (Note: The access date “April 22, 2025” appears as cited in the original text and associated footnote context.)

Works Cited

ABC News. 2014. “Oscars 2014 Results: Complete Winners’ List.” ABC News. March 3. https://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/oscars-2014-results-complete-list-academy-award-winners/story?id=22740618.

British Broadcasting Company. 2016. “The 21st Century’s 100 Greatest Films.” BBC Culture. August 23. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160819-the-21st-centurys-100-greatest-films.

Brown, Peter. 2014. The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity. Enlarged ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

De Kraker, Benjamin. 2024. Post on X. May 21. https://x.com/BenjaminDEKR/status/1792869755835019530.

“For Claude Desktop Users.” 2025. Model Context Protocol. Accessed April 22. https://modelcontextprotocol.io/quickstart/user.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 2008. Metaphors We Live By. 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Love in Time of Replika. 2023. Hi-Phi Nation. Season 6, episode 3. https://hiphination.org/season-6-episodes/s6-episode-3-love-in-time-of-replika/.

Luhrmann, T. M. 2020. How God Becomes Real: Kindling the Presence of Invisible Others. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Orsi, Robert A. 1998. Thank You, St. Jude: Women’s Devotion to the Patron Saint of Hopeless Causes. Rev. ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sam Altman (@sama). 2024. Post on X. May 13. https://x.com/sama/status/1790075827666796666.

Silberling, Amanda. 2024. “Why AI Can’t Spell ‘Strawberry.’” TechCrunch. August 27. https://techcrunch.com/2024/08/27/why-ai-cant-spell-strawberry/.

Suleyman, Mustafa. 2024. “What Is an AI Anyway?” TED. Video, 15:47. Posted April. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKNCiRWd_j0.

Zao-Sanders, Marc. 2025. “How People Are Really Using Gen AI in 2025.” Harvard Business Review. April. https://hbr.org/2025/04/how-people-are-really-using-gen-ai-in-2025.