A paper on colonial histories and today’s foreign policy debates

According to mainstream historians, the era of colonialism is over. Today, former colonizing powers—including the United Kingdom, the United States, Russia, France, Spain, Portugal and Germany—all pay lip service to the self-determination of their former subjects. And yet, as Joram Tarusarira points out, new rhetoric doesn’t change the fact that the balance of power between former colonies and former colonizers remains largely the same. In the article “Religion and Coloniality in Diplomacy,” he writes:

Recent research in the sub-field of religion and international relations suggests that colonialism’s legacy has profound and residual influence on issues such as security, promotion of the right to freedom of religion or belief, gender equality, sexuality, and reproductive health and rights.

The Problem of Coloniality

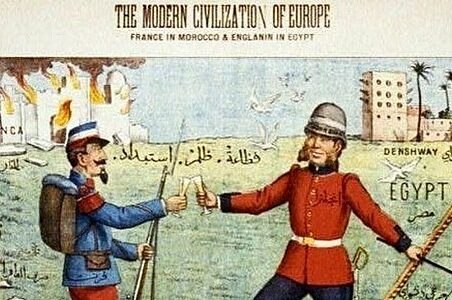

A perception pervades contemporary global political relations that modern (Euro-American) civilization understands itself as the most developed, superior civilization. This sense of superiority “obliges” it to “develop” (civilize, uplift, educate) underdeveloped civilizations.

In his paper, Tarusarira distinguishes between colonialism and coloniality. Colonialism can be understood as the historical period during which global powers, predominantly in Europe, openly sought to exploit the people, land, and resources of less powerful nations under its control. Although historians mark the end of this period around the 1970s, the same colonial powers that exploited the populations of the Global South for generations continue to exert virtually insurmountable control over the global economy, military balance of power, and international institutions such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. Given this, Tarusarira distinguishes coloniality as the “ideological frameworks” that sustain colonial relationships to this very day.

Religion vs. Secularism: A Colonial Distinction

Often lurking behind discussions about the right to freedom of belief or religion…is the question of who gets to decide . . . . and who benefits from the process . . . . The modern understanding of religion as a distinct and autonomous sphere of life is intimately entangled with colonialism and coloniality.

The very notion of religion, in the author’s analysis, is “a historical construct that emerged in the West.” He points out that colonial powers sought to define religion as something distinct from other human endeavors. European colonizers increasingly aligned their interests with objectivity and superiority while framing the practices and belief systems of other societies as subjective and inferior. At the very same time, Europeans incorporated Christian concepts and assumptions into the moral claims of the emerging body of international norms and laws. In other words, the very framework of the international order reflected European religious subjectivity, while minimizing and exploiting people with other spiritual and cultural beliefs. Far from being objective, many of the ideas within dominant secular principles are rooted in Judeo-Christian morality.

Recommendations

Tarusarira offers several proposals to policymakers to help them avoid continuing colonialism’s legacy in foreign policy and religious affairs. Those proposals include the following:

- Address extremism as a challenge that all societies and cultures face: Rather than merely focusing on Islamic extremism, an emphasis rooted in Islamophobia and Orientalism, it is important to also address forms of cultural and religious extremism in the West, including white nationalism.

- Take a truly objective look at religion: The author recommends appreciating that religion is neither inherently violent nor peaceful.

- Reframe human rights: It is important to acknowledge that concern for and advancement of human rights is not a European invention and that it is possible to safeguard human freedom in many different, context-specific ways.

- Emphasize local voices and practices to improve quality of life: Indigenous actors have context-specific approaches to addressing human rights issues that may be more effective and applicable than approaches that outside actors impose on them.

You can read “Religion and Coloniality in Diplomacy” in full below. This report was one of many commissioned by the Secretariat of the Transatlantic Policy Network on Religion and Diplomacy (TPNRD). The full body of TPNRD reports, along with policy briefs and other resources, can be accessed on its website Religion and Diplomacy.